From Conservation

In keeping with this year’s Heritage Open Days theme of Astounding Inventions, I focused the content of my section of the tours on the influence of historical innovations in the development of the book. Of course, this is a potentially vast subject, but using examples from the Archive collection I split the topic into three eras: Pre-industrialisation, the Modern evolution of the book structure and the Industrial Revolution.

Bound texts were precious luxury items and bindings were finely-crafted and decorative objects reflecting their rarity and the time and expense that went in to producing them. Before paper arrived in Europe in the 12th century the writing surfaces were vellum/parchment made from animal hides and all the text was inscribed by hand.

However, stationery books were by necessity much more humble and affordable. The limp vellum binding style was used for centuries. As the name suggests, the covers are made from vellum, unsupported by boards. Earlier examples also have vellum pages, but later ones often have paper pages. The design is simple and utilitarian – a protective and portable format to record written information.

As an archive, most of our collection focuses on manuscript rather than printed works and stationery volumes rather than what could be termed ‘library’ books. As such we have plenty of examples of limp-vellum bindings.

Two huge developments influencing book binding in Britain occurred between the 15th and 16th centuries. In the late 1400’s, papermaking finally arrived in Britain. In England the mill of John Tate in Hertfordshire produced paper as early as the 1490’s. It was followed by that of John Spilman in 1588 at Dartford, Kent. (The first recorded European paper-mill was at Xativa in Spain, which is thought to have been established about 1150).

And it’s difficult to overstate the importance of the ‘printing revolution’ which began around 1440 when German goldsmith, Johannes Gutenberg invented the movable-type printing press. After its invention it was disseminated rapidly through Europe and printing arrived in Britain with William Caxton’s press in Westminster, in 1476.

The dominant style of binding until the eighteenth century was the tightback, where the leather spine-cover material is adhered directly to the spine, the sewing supports are generally raised cords and there are no visible joints where the boards meet the spine. This is still the typical style favoured for fine-binding today. As the number of books being produced grew exponentially due to printing, the craft of bookbinding became ever more refined. Historically the production of a book was divided between several separate operations: the paper-maker, the printer and the book binder. Consumers would buy their books un-bound and take them to a binder to have them bound in the style they specified.

The next innovation in book structure was the hollow-back. By creating a hollow space in the spine lining, the spine cover material is able to remain flat while the spine moves as the book is opened. A flat spine cover also allows for more decorative potential. There still exists mechanical stress on the joints of the book, but the spine cover does not suffer from the vertical splitting often seen in tightback styles.

One particularly neat adaption of the hollow-back style is the springback. Patented in England in 1799 this sturdy style of stationery ledger is recognisable by it’s thick head-caps and thick boards. The springback’s great innovation is the curved spine piece (the spring) and lever mechanism which allows a book to ‘spring’ open, allowing it to lay fully flat for writing in and providing full access to the pages – a necessity for hard-working books being opened and written in on a daily basis. The mechanism is somewhat complex to construct but the result is a very robust book. We have many springback stationery books in the collection.

Finally, we have to look at the Industrial Revolution where the book finally becomes the consumer object we know today. As literacy and the consumer class grows, so does demand for books. Dissemination of technical knowledge in affordable mass-produced books is both a product of and a driving force of the Industrial revolution.

Technologically there were two great leaps in book production – the cast-iron press and then the steam-powered cylinder press. By 1800, Lord Stanhope had built a press completely from cast iron which reduced the force required by 90%, while doubling the size of the printed area and doubled the output of the old style press. The Stanhope iron press was a game changer, allowing faster and higher quality printing but it still had the limit of only printing one sheet at a time. The next technological leaps came together with the 1812 debut of Friedrich Koenig’s cylinder press. This new steam-powered printing press could print up to 1,100 sheets per hour, printing on both sides of the paper at the same time.

Papermaking had to adopt new sources of cellulose and technologies to keep up with demand. After the mid-1800’s paper quality and longevity makes a sharp decline due to the inclusion of wood-pulp.

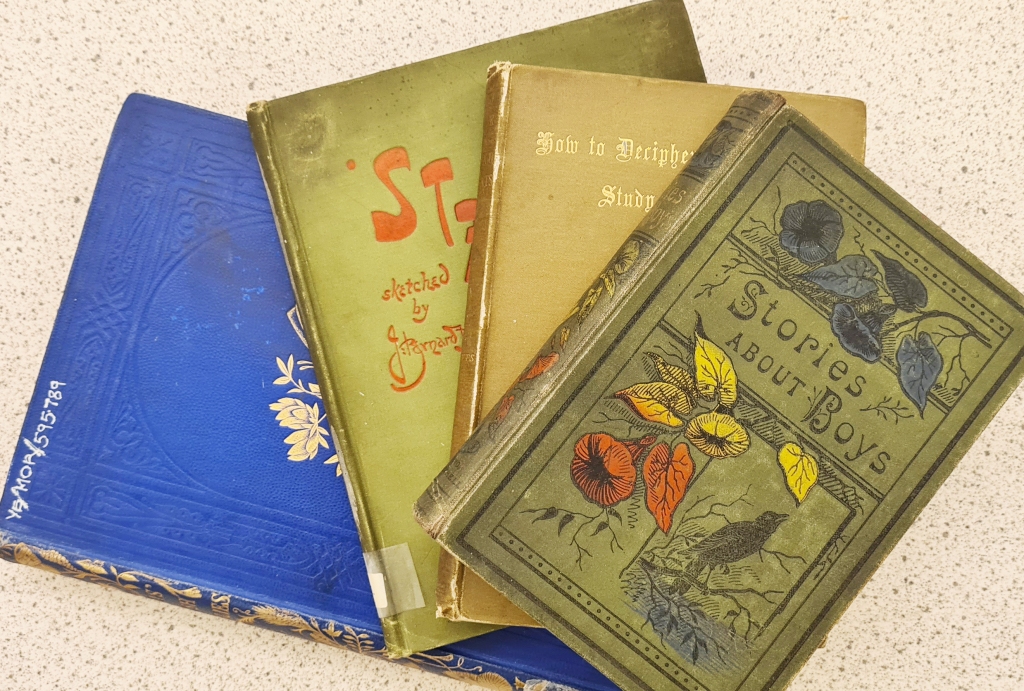

In the 19th century publishers took over book production and binding. In 1823 cotton book cloth is developed, along with the case-binding style. 19th century case-bound books often have quite attractive block-printed cover designs, and for the first time, book covers reflect the contents of the book.

Of course, there have been many other developments in materials and techniques during the development of the book and I’ve only scratched the surface in this post!

Thanks to everyone who attended the tours on the day.

by Kat Saunt

Conservator